The following post discusses the recent controversy surrounding Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel Maus, the aftermath of the Shoah, and the ongoing violence in Ukraine. As such, we’re including a general content warning for intense themes and imagery.

As I write this, I am sitting in a cafe near my apartment in Providence, Rhode Island. No one is dropping bombs on us, as I have grown increasingly fond of saying to my eight-year-old daughter, especially when she gets upset about something trivial. On my headphones, Einsturzende Neubauten’s epic “Headcleaner” momentarily bangs away the grieving rage I have been in all week watching Russia invade the country of my grandmother’s birth; on my phone, a video clip of elderly Jewish women Holocaust survivors sheltering underground in Kyiv, cursing Vladimir Putin as his bombs rain down on their city. Any one of them could be my grandmother.

If only she were alive to learn that the country of her birth has a Jewish president now, thank fuck she is not alive to see what is happening there, to see any of what has happened in the years since her peaceful death in her Manhattan apartment. She died in 2004, after a short decline, in her nineties, in apartment 27M of her building in Lincoln Towers. Einsatzgruppen could not kill her, nor could later waves of Nazis across Galitzia, and later, cancer gave up and left her alone, too. She witnessed the liquidation of her entire ghetto from the hiding place her Ukrainian friend had given her, she survived much of the war hiding in the woods, she rebuilt her life in DP camps, and then the Jewish quarter of Paris, and then the Grand Concourse in the Bronx. After she died, I found a letter from the family physician, a survivor himself, stating that she had been beaten so badly in a Nazi slave labor factory that she should not work outside of the home. She never told me she’d been enslaved in a Nazi factory.

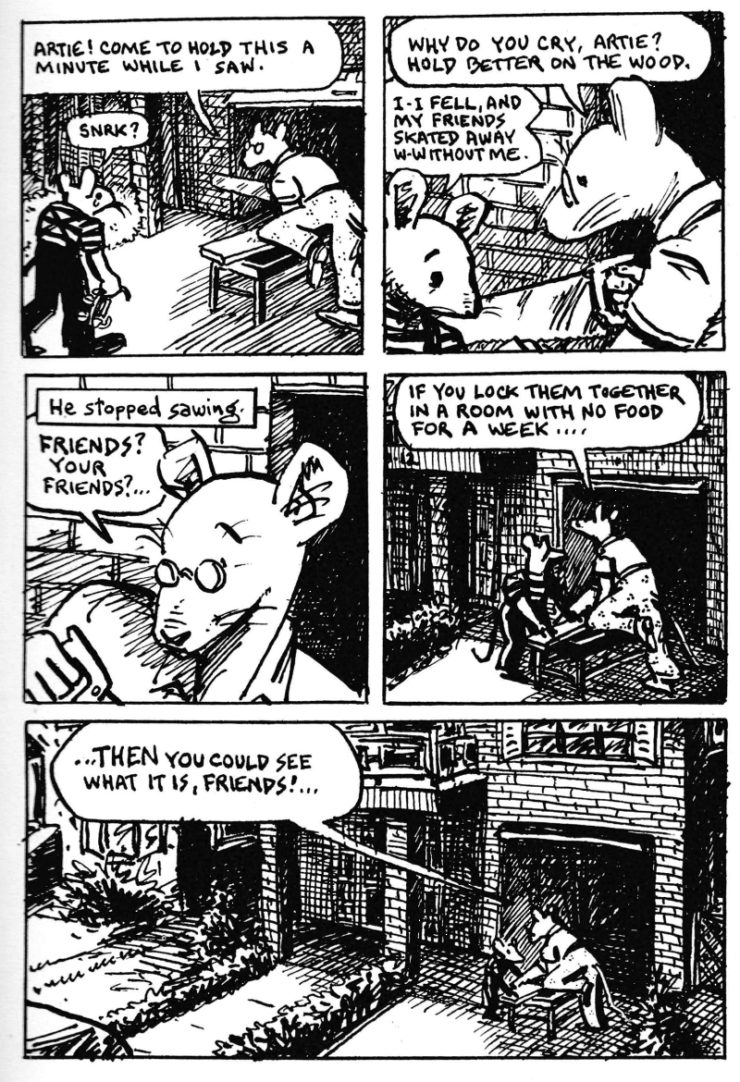

It’s January, 2022. The McMinn County School Board votes to ban Art Spiegelman’s Maus because of its “use of profanity and depictions of nudity”. Among the specific objections were board members saying: “…we don’t need to enable or somewhat promote this stuff. It shows people hanging, it shows them killing kids, why does the educational system promote this kind of stuff, it is not wise or healthy…” and “…a lot of the cussing had to do with the son cussing out the father, so I don’t really know how that teaches our kids any kind of ethical stuff. It’s just the opposite, instead of treating his father with some kind of respect, he treated his father like he was the victim.”

Do I need to remind you what Art Spiegelman’s groundbreaking comic Maus, is about? Of course it is about his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz, a Polish Jew like my family. It’s about something else, too. Something you’d only know about if you’re like my family. I’ll get to that. For now what I want you to know is that every survivor family has a Vladek or two, an elder locked down by trauma, who holds more in secret than they share. My grandfather, Mendel Lipczer (Max to Americans), was mine. I recognized in Vladek the sudden rages, the emotional hardness, the Members Only jacket. So Maus is about my family, in a way, though Mendel was never in Auschwitz. As far as I know, anyway. That man told me as little as possible. I know tantalizing fragments about his life during the war, but he didn’t want me to know much. Or he couldn’t speak of it. How could he bridge the gap between us, me a kid in New York in the 1980s, him an old man born in Poland when it was still part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire?

Trauma is exhausting. Between the closest of friends or intimates, it can be nearly impossible to convey. I can only imagine the impossibility my grandparents must have felt across the gulfs of horrific personal experiences of genocide, a language barrier, and the huge cultural distance between us. So now I imagine their nights, of sleepless memories and hard dreams, and I wish to enter them and learn what they were unable to tell me.

I did try, when they were alive. And I learned a few things, either by accident, like my grandmother’s story about the liquidation of the Sambor ghetto—the act of telling it caused what I now recognize as a trauma reaction, and so I never asked her anything again—or because my grandfather was in a talkative mood and felt like telling me something small before shutting back down again, the omissions greater than anything revealed: he beat up a man for stealing coats and flour from Jews, somewhere in Western Ukraine. Or, the old man in a prison cell with him who yelled at their German captors, “Kein mensch!”. Or, when they all emerged from the forest in 1945, the men only had one clean shirt between them, so they took turns wearing it to get married in, right there at the edge of the woods, one man unbuttoning it and passing it to the next man.

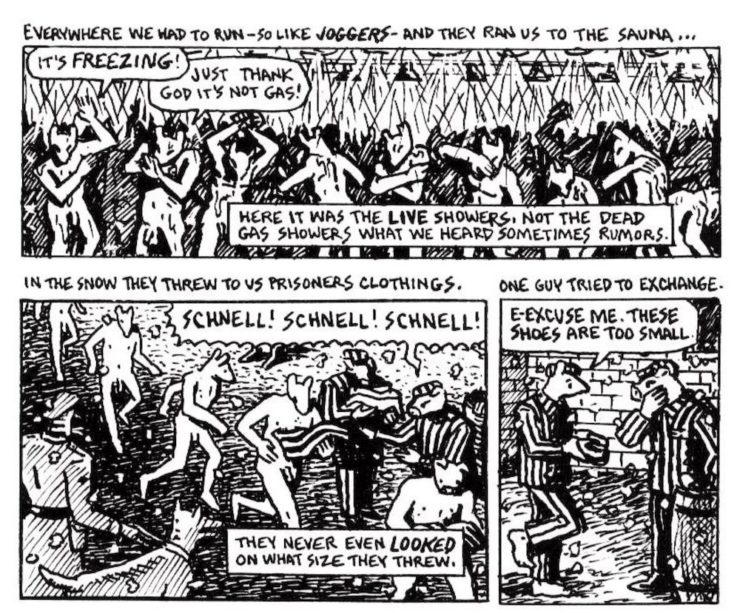

Let’s talk about that. Maus is almost ubiquitous now, in school curricula and in the serious comics canon. Maybe you’re Jewish and read it because it’s part of our story. Maybe you had to read it in middle school or high school. When you read it, did you understand what a monumental task it must have been for Spiegelman to drag that story out of his father? Have you ever met any Vladeks? Do you know what it means to get them to talk at all, let alone that much? And believe me, you’re all lucky Spiegelman used animals to tell the story. It’s like a pill pocket, blunting the grotesque brutality he’s depicting.

I despair of outsiders really understanding Maus. What would someone on the McMinn County School Board make of the moment when Vladek tells a young Art to see what happens when people are starving: “Then you could see what it is, friends.” Every survivor’s kid knows that moment with their elders. Every survivor’s grandkid knows it, too. Anyone who has family who survived a war or a genocide will know it; it is not limited to Holocaust survivors. But what would a comfortable person know? It is the silence of the comfortable that allows us to keep filling mass graves. There’s a reason book-banning is so popular among Fascists.

You want it to be a movie. You want so badly for it to be a movie. You want your hand held, you want clear protagonists and you want to know They Made It. Well, they made it, and then they kept living, carrying their invisible corpses and the visible bullets lodged irretrievably in their flesh. They made it, to Paris or Toronto or the Grand Concourse or back home to the family apartment in Turin, and some of their “movies” ended in a lifeless heap at the bottom of a staircase, or a blood-filled bathtub in Queens. They made it, along with all the inexpressible weight of a destroyed culture, to small apartments all over the five boroughs, a silent black cloud above all proceedings. I drank their pain along with my grandmother’s borscht. The people who want to remove Maus from the truth-hungry eyes of teenagers want a Christian redemption arc, one that no doubt ends in a climate-controlled house with a manicured lawn down the road from a shopping mall. But the world is a mass grave, heaving with corpses. Put as much turf on it as you want. The bones will still rise.

There’s a government building in Ohio constructed with bricks made from earth that had been an Indigenous burial ground. The bricks contain their bones. There is a neighborhood built where the Warsaw Ghetto once stood, whose bricks are constructed from its rubble. The bricks contain fragments of the bones of the Ghetto dead. The bones will still rise. We live among them.

Our beloved elders barely spoke of what they had seen and been through, except in fragments that I’m still putting together. Their bodies told the stories. An uncle was missing a few fingers. Mendel had bullets in him that had never been removed, from one of the multiple times he escaped a death march by running into the woods. In family photos from the 1950’s, my grandmother grips my mother’s upper arm so hard, it hurts to look at. She was pregnant in the final months of the war, in hiding, in the woods, in the Polish winter. My aunt was born in a DP camp a few months after the Soviets liberated Poland, with a rare bone disease that later returned as a tumor in her heart. Do you know how monumental a task it must have been for Spiegelman to get his father to give him a book’s worth of story, in words?

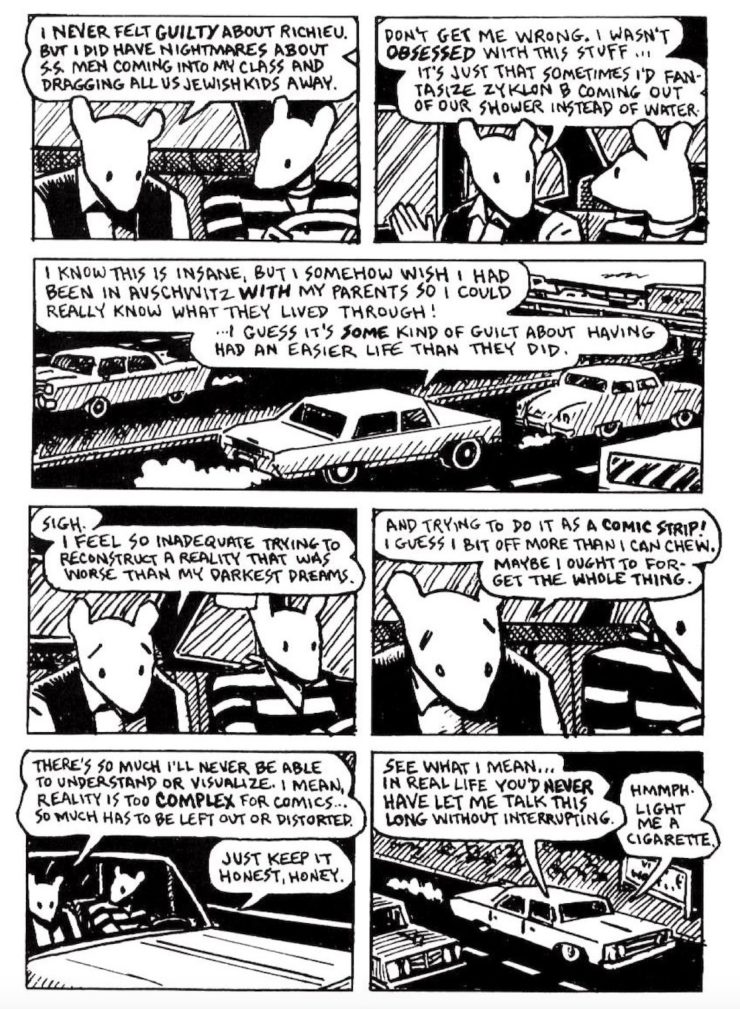

In fall of 2020, as COVID and white nationalism raged unchecked, and we waited in dread to vote out the white supremacist president, I taught a course in the Jewish Graphic Novel at University of Florida. I tried very hard to include works that were not about the Shoah, but I made it a point to teach Maus. I hadn’t revisited it in a long time. What struck me before anything else is how incredibly well-written it is. It tells a story about Jewish life in pre-war Poland in granular details that felt obvious to me when I read it as a teenager, but which I now understand are alien to most readers. Something else struck me on that re-read: Maus is as much a story about second-generation trauma as it is about a lager survivor’s direct experience and resulting trauma. This, again, is a granular detail that felt as familiar to me as a limb, growing up.

My mother hoards food, in neatly organized stacks. She had a hair-trigger temper when I was a child. It felt impossible.

My grandparents lived with as few material possessions as possible. They were never happy. It felt impossible.

My mother’s cousin tells me that one day her father, my grandmother’s brother, who also hid with them in the forest, threw all of the family’s dishes out of the window of their Bronx apartment, in a rage. I recently told an American friend of mine about that. He said, “My god, all of those apartments, each filled with so much pain.”

Trauma is not gentle. Survival is not redemption. Redemption is a lie.

It’s November, 2019. I’ve just returned from a life-changing visit to Poland, where I attended a ceremony dedicating a new memorial to the slaughtered Jews of Grybow, my grandfather’s tiny town in Galitzia, in the Jewish cemetery overlooking the town. I learned things I’d never known about my family on that trip, specifically that twenty-five of them had been killed in a massacre I’d never heard about, in nearby Biale Nizne. Now I’m home, sitting across my dining room table from a visiting colleague, a Jewish author I’ve known for years. In between sips of wine, they fix their eyes on me and tell me, “Jews need to stop talking about the Holocaust.” This is not the first time they have stared me down and said that. The time before this, I’d been in mid conversation with another friend who had just asked me what I was working on, and I’d been telling her about my graphic novel in progress, an accidental body-horror comic partially set during the liberation of Buchenwald, when they interrupted me to say it. This time, as they talked over me endlessly, my eyes went to my boots by the door, still crusted with mud from the mass grave of Biale Nizne, where my great-grandparents and many of my aunts and uncles lie, including a baby, and a teenage girl, people I would have known and loved. There is silencing within communities, as well. This is not the place to discuss it in detail, but I’ll simply say here that the impulse to silence Holocaust descendants is a very American one, whether it comes from other Jews, or from a school board full of gentiles who are offended by the realities of our elders’ lived experiences, and by the ways in which we must tell them. For both, the Shoah is an abstraction.

It must feel good to have an abstract relationship with history. What a privilege. But this is not a movie, and history is a misleading word for life. In my life, the people in Grybow, in Nowy Sacz, in Krakow, could have been my neighbors and friends. Now we, the third generation, try to connect with one another, free from the weight of shame and resentment that the second generation, our parents, carried. There is extreme pain in the knowledge that we could have known and loved each other sooner, that we could have grown up together, that we were severed from one another. This is not a movie. Redemption is a lie.

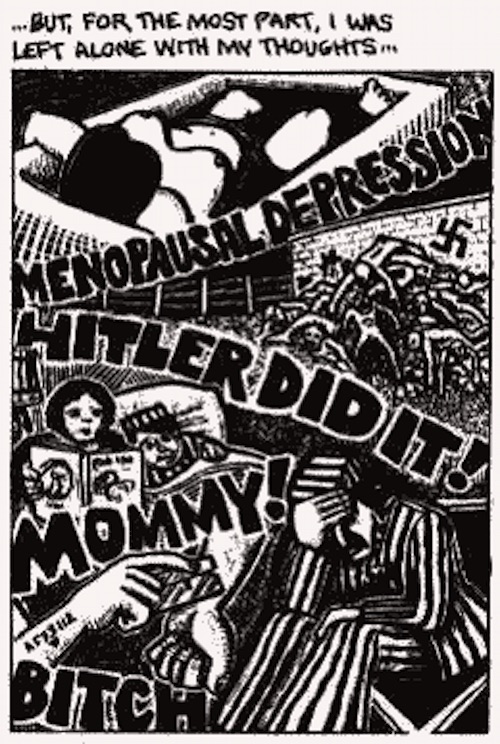

I was a teenager when Maus won the Pulitzer. A few weeks before that, I had just discovered Raw, the now-legendary art comics anthology edited by Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly. Raw dropped into my life like a bomb, and detonated. There’s an excerpt from Maus in Raw, one of the parts of the story that the McMinn County School Board objected to, in fact, “Prisoner On The Hell Planet.”

Though the title recalls EC Comics, an earlier generation of comics by traumatized artists that scandalized people who like Nice Stories, the artwork is Expressionist in style. The story is Ashkenazi in the extreme: Spiegelman’s mother Anja, also a lager survivor, comes to Art in a moment of emotional need; he rejects her. Later, she takes her life. A young hippie Art reads the Tibetan Book Of The Dead over her coffin, then finds himself imprisoned by his guilt. It’s a remarkable comic. I didn’t understand that when I first read it, because it seemed so normal to me. So matter of course. I recognized the suffocating emotional weight of Anja’s sadness and love, though I could not have named it at seventeen. I now also recognize her lifelong grief as the mother of a dead firstborn; I am one, too, and I also recognize the unfair burden our trauma can place on our living children. I recognized the resentment, because my mother felt that towards her survivor parents. The prison of guilt, well, we’ve all built one in our hearts, and anyone who says they haven’t is lying or dead. Redemption is a lie. We resent our suffering loved ones for the weight they put on us. The guilt is unending.

This is what I’m trying to tell you, and likely failing to: Maus is remarkable, but to the children and grandchildren of survivors, it felt like us. It’s a family story. Most of our family stories were locked behind the silent faces of our elders, and now reside in their graves. What’s remarkable about Maus is that it was told at all.

Buy the Book

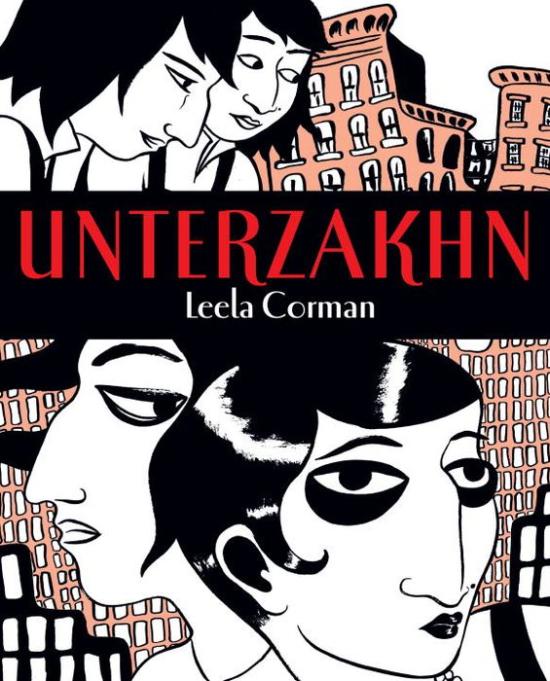

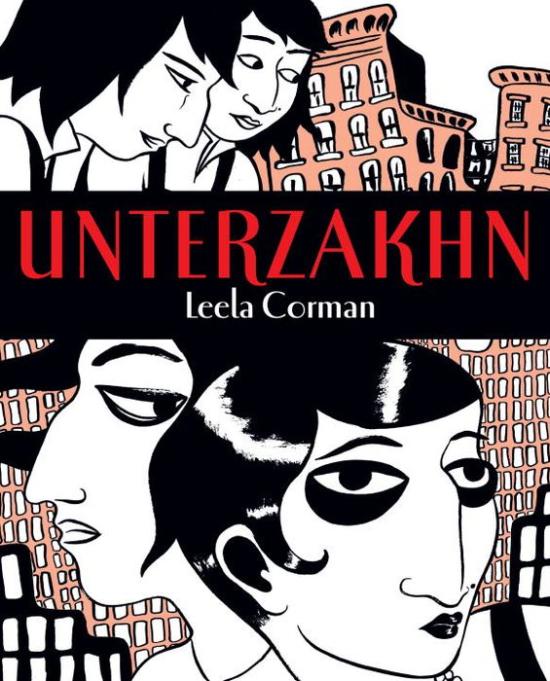

Unterzakhn

Leela Corman is a painter, cartoonist, and educator. She lives in Providence, RI with her family and a violent little cat. She is the creator of numerous works of short nonfiction comics on trauma, history, and rock & roll, and the graphic novels Unterzakhn (Schocken-Pantheon 2012) and the upcoming Victory Parade. Find her on Twitter and Instagram